CROSSINGS - Essay by Anne-Louise Willoughby

“Big sky, big road, big desert, little Koko...

At times on the Eyre Highway (all 1,600 plus kms of it), you feel very small, dwarfed by the ‘magesterial’ wilderness that surrounds you, and the shift in colour and light of its moody skies.

The actual Nullarbor Plain is just one treeless segment (I hope to reach it in a week) of the highway, but locals refer, reverentially, to the whole legendary stretch from Norseman to Ceduna, as simply, 'The Nullarbor'.

Walking along it, and particularly often camping in its midst, you can sense the sacred nature of the place, its geographical vastness and stark beauty.

The night skies, riddled with myriad winking stars.”

Tom Fremantle, world walker (2023).

The lure of a desert crossing has enticed travellers for millennia. Psychologist Robert Wicks writes that one of the most fascinating groups of spiritual guides in history was the fourth and fifth century Fathers (Abbas) and Mothers (Ammas), ancient desert monks of the Persian and Northern African deserts. They didn’t want their perspective to be dominated by the culture of the time and instead sought simplicity and purity of heart. Perhaps the lure of a desert crossing today has, in part, components of the spiritual which at its heart often reflects the desire to break from habit, to escape the chains of modern life. When undertaken by choice, a desert crossing offers an opportunity to return to the fundamentals of the moment when human engages fully with the natural world.

The level of that engagement will depend on how much kit is involved – vehicle, camper, caravan, motorbike, bicycle, or perhaps hardy foot ware as in Tom Fremantle’s case, along with his baby buggy kit holder, Koko. For the adventurer, the athlete, or the traveller en route, the impetus for the crossing will differ in tone. It might also depend on whether there is a goal attached – fastest crossing, first crossing in a certain mode, a fundraising objective, or maybe a group initiative, just the need to get from A to B, or perhaps a self-discovery tour. Whatever the mode of transport or desired end result, there will inevitably be a moment when the grandeur, the vastness, and the apparent ‘emptiness’ of a desert crossing will register. I have crossed the Nullarbor – Oondiri as it is known by traditional owners – a number of times in various vehicles. The moment when the rhythm of the desert landscape seeps into your soul arrives with the acceptance of the distance you must navigate. There are the kilometres on the odometer then there are those in your mind’s eye, the thought flow, and the slowing of the impulses that run your everyday – a desert crossing, in whatever mode, shifts your body’s gears. The ‘emptiness’ is a fleeting notion as the desert leaps into hyper focus and draws you in. I think Kant might have something to add here about the sublime, but that is for you to explore.

Cyclist Arthur Richardson speaks of his love of adventure and pioneering work as primary drivers of his desert crossings in the late 1890s and, as I write, modern day adventurer Fremantle is a few hundred kilometres shy of completing his solo walk across Australia as part of his attempt to walk around the world. Tom is a generous man and ties his wanderlust to great causes raising funds while crossing deserts and circling war zones. He has shared in real time his experience of walking across the Nullarbor – a little different from Richardson’s record of his second crossing published in booklet form in 1900 by his sponsors, the Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Company, entitled ‘The Record of a Remarkable Ride’. While Richardson’s maps were a valuable pioneering resource, Fremantle had the benefit of the macadam, the roadhouses, truckies, grey nomads, cyclists, and other enthusiastic passers-by. He does, however, have only his two feet to propel him rather than Richard’s Dunlop pneumatics on a new-fangled contraption:

“When I bought a machine in 1896 and learned to ride it,” he remarked, “and three weeks later expressed my intention of doing what no other cyclist had done across, via Eucla and Port Augusta, to Adelaide, those who heard of it called me foolhardy and, after vainly endeavouring to dissuade me from making the attempt, predicted that I would not succeed. Succeed, I did, however, and to show that the feat was not an impossible one, but merely one which required to be done …”

As Fremantle began his solo walk across Australia, pushing his supplies and meagre camping equipment in the converted baby carrier, he posted on his Instagram page, his virtual travel diary. He speaks to the ideas of isolation:

When Apollo 11 astronaut, Michael Collins, was left manning the spacecraft while his more famous crew mates, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, walked on the moon, he was described as ‘the loneliest man in history’. I think he certainly earned this title back in 1969 - and, through that historic moment, he still probably eclipses all others when it comes to human isolation.

Perhaps the closest us earthlubbers can come to Collins' unique social dislocation is when we sail alone into the high seas, or scale a remote mountain, or bivouac in the midst of the desert or the jungle.

Certainly, camping alone in the Australian outback is at first daunting: the burr of cicadas, the red earth, the green and bone white gum trees, the exquisitely lit, at times apocalyptic, evening skies.

But, once you have set up camp, often early (it is fully dark by 6.30pm now) and boiled pasta and brewed tea, you relax and savour the moment. Solitude, yes, but not really loneliness. It's been a punishing but positive few days walking the 180 odd kms between the little mining towns of Southern Cross and Coolgardie, including a few wild camps.

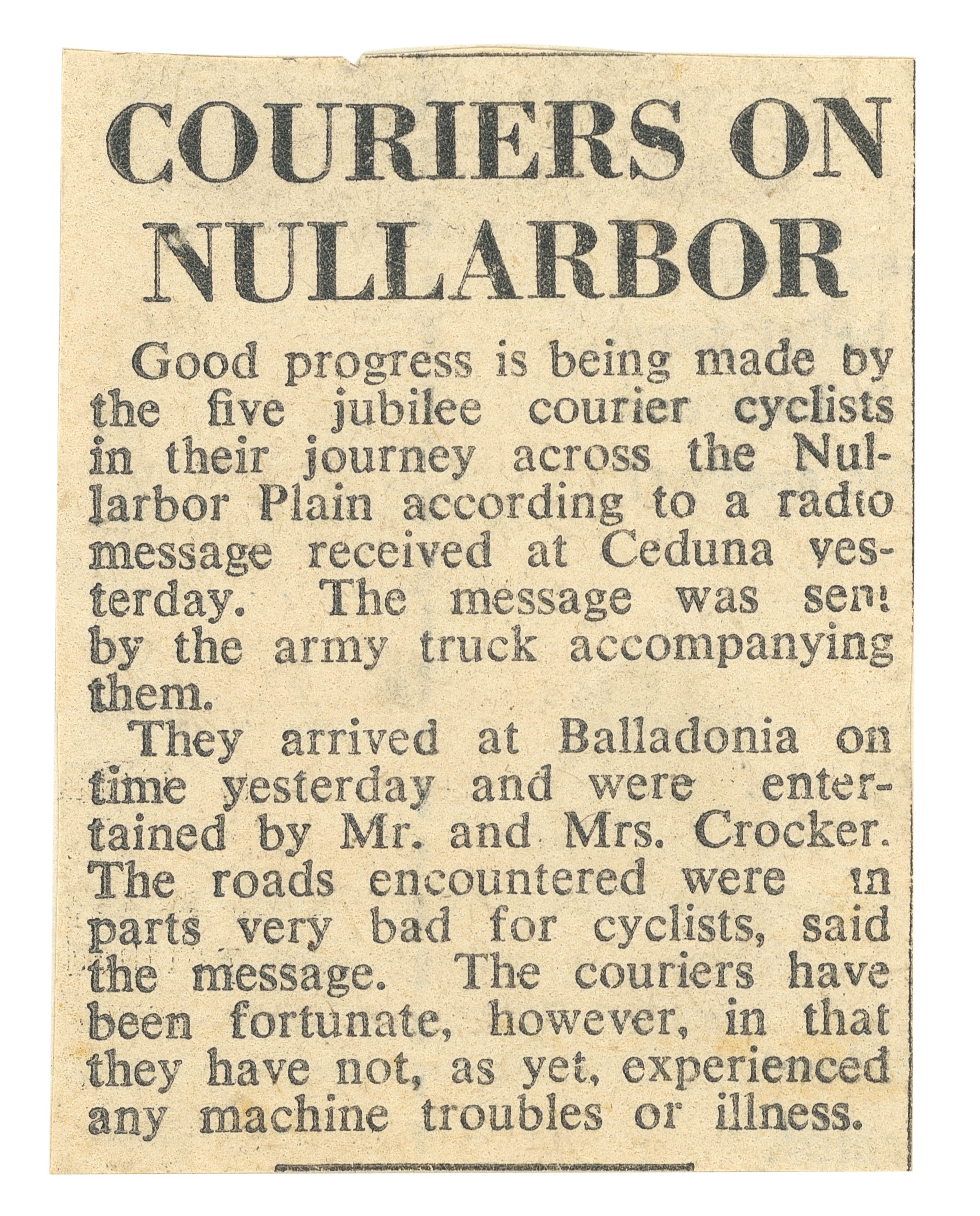

The Nullarbor covers approximately 180,000 square kilometres, and the treeless plain about 52,000. At its widest point from Norseman in the west to Ceduna – Tjutjuta, meaning resting place – it extends1,200 kilometres. Three quarters of the Nullarbor is in WA. By the time Fremantle reaches Sydney he will have walked over 3,500 kilometres in a four-month trek. His trusty buggy has received maintenance along the way – the last being in Wagga Wagga at Kidson’s Cycles by team member Rohan who said, “All the cross-country cyclists and walkers end up here – we attract you crazies but always try and fix you up.” Fremantle writes that he met Douglas de la Concha ‘in the middle of nowhere on the Nullarbor’. Concha is attempting a Guinness Book of Records ride to be the fastest round the world cyclist on a one gear bike (covering 165kms a day) and was also a satisfied Kidson’s customer. Seven cyclists crossed Fremantle’s path as he walked the Nullarbor – a round the world rider who had covered 30,000 kilometres from Japan, two Australians, two Germans, a Brit and de la Concha, a Hawaiian. It was a different story for the first recorded crossing on foot, as Fremantle reflects:

"A hideous anomaly, a blot on the face of nature...”

This is how the explorer, Edward John Eyre, described the Nullarbor in 1841, after becoming the first recorded person to cross the vast plain with his indigenous colleague, Wylie.

Now, the 1600 odd kms Eyre Highway, stretching the Nullarbor and beyond, which I have just finished walking, is named after him.

The sky was moody as I crossed into the little harbour but my mood was elated as I thought back to all those days walked and nights camped in the bush: the wind, rain, sun, rainbows and lately frost; the dingoes, wild goats, roos, emus and a plague of mice; the ghost gums and spinifex and mulga stumps; the big jinker road trains, the camper vans and once in a blue moon, bicycles; the red dirt and dirty clouds, the star spangled nights and noon skies of fathomless blue, the pure, if sometimes misty dawns and the rusty dusks.

Yes, it will take time to shake off the Eyre Highway's beautiful grip on my memory.

I can imagine Tom Fremantle sitting down with Scotchie Wright for a chat about being the first cyclist to ride from Fremantle, named for Tom’s ancestor Captain Thomas Fremantle, to Adelaide. Resting under the same night skies of the ancient plain what would they make of each other’s quests? Tom Fremantle has cycled from Swanbourne in Buckinghamshire to Swanbourne in Perth, while not at the pace of Hubert ‘Oppy’ Opperman’s crossing from Fremantle to Sydney in 1937, there would be much to discuss. Needless to say, Oppy and Wright may share this sentiment on Nullarbor crossings from Fremantle:

If my walk was plain sailing, like a steady pulse, it would be very dull. You need the peaks and troughs, the blood and dirt, the sun and rain, the dead on your feet, howl at the moon moments as well as the many blissed out, euphoric ones.

Whenever the walk is tough going, I always try to remember how hugely lucky I am to be doing it. Many dream of such travels but never have the chance: I need to be true to all those dreams.

Anne-Louise Willoughby

References

Wicks, R.J., Crossing the Desert: Learning to Let Go, See Clearly, and Live Simply, Sorin Books, New York, 2008.

Richardson, A., ‘The Record of a Remarkable Ride’, The Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Company of Australasia Ltd, Sydney, 1900.

Fremantle, T.F.H., @tomfremantle, 2023.

https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/opperman-sir-hubert-ferdinand-oppy-28107 , accessed 19 September, 2023.